Carlo Caloro: «Non solo intenzional.mente»

di Gabriele Perretta

Qual è la reale entità dell’inganno artistico che subiamo o «pro.creiamo»? Soprattutto in quei settori dove circola tanta astrattezza? Maggiori sono gli interessi e le seduzioni iconiche e particolarmente crudele potrebbe risultare il raggiro perpetrato ai danni delle migliaia di “creativi potenziali” che si aggirano tra le popolazioni di Android. Nell’ultimo anno negli Stati Uniti, 300.000 persone hanno scelto di inserire i dati circa le loro mansioni in un sito che verifica le loro attitudini e versatilità operative, per valutare il rischio che corrono di perdere il lavoro a causa dell’automazione e dei robot. A lanciare l’allarme nel 2013, erano stati Carl Benedikt Frey e Michael A. Osborne, i quali in uno studio avevano previsto che, nel giro di dieci o venti anni, circa il 47% dei posti di lavoro negli Stati Uniti sarebbe stato completamente automatizzato.

Un allarme eccessivo? C’è chi risponde a queste previsioni, considerate allarmistiche, segnalando come nel 1870 circa l’80% dell’intera forza lavoro statunitense fosse impiegata nell’agricoltura; successivamente, a seguito dell’introduzione dei trattori, e quindi dell’agricoltura estensiva, si verificò un esodo biblico dalle campagne, ben raccontato da Steinbeck in Furore. In pochi anni, però, questi contadini e i loro figli trovarono occupazione nell’industria ed oggi l’agricoltura americana, con meno del 2% degli occupati, è tra le più produttive del mondo. Le macchine, i robot e l’intelligenza artificiale, secondo i faciloni, creano maggiore produttività e, quindi, maggiore benessere; nello stesso tempo chi perde lavoro lo trova nell’industria, nelle prestazioni d'opera o nel campo sempre meno indistinto dell’operatività artistica o del terzo settore? A conferma di questa tesi, viene citato il fatto che il mondo occidentale e l’industria culturale che lo relaziona è più avanzato ma anche più rischioso, più sospettoso ma anche più votato alla promessa della piena occupazione.

Tutto bene, quindi? Vogliamo o non vogliamo, ci piace o non ci piace, siamo ormai nell’era post-industriale in cui le macchine svolgono - e svolgeranno sempre più - quasi tutte le attività pratiche e ripetitive. L’unica prerogativa che resta all’essere umano è la creatività, robot permettendo. Per gli artisti – che appaiono fortunati, in questo trend - i cambiamenti hanno una doppia natura. Da un lato, dobbiamo considerare cosa è cambiato direttamente per le persone: per esempio, il fatto che i nostri occhi si posano oggi sempre più spesso su nuovi orizzonti progettuali, dove valgono regole diverse rispetto a prima. Dall’altro lato, dobbiamo considerare che la «controrivoluzione dell’industria dei media tradizionali» ha influito sulla nostra comprensione del nuovo, con la paradossale conseguenza che l’innovazione, oggi, è prevalentemente raccontata da chi la subisce, e non da chi la fa.

Dobbiamo, quindi, barcamenarci tra la nostra percezione diretta del mutamento tecnologico - dove a volte scoviamo delle opportunità per migliorare la nostra vita - e la visione distopica presente nel grido artistico dei media tradizionali e dei suoi “artigiani”, che dopo anni di dominio del nostro tempo libero si sentono “sostituiti”. L’esperienza artistica diretta è, quindi, del tutto improvvisata, la nostra reazione non è né “educata”, né “strutturata”, proprio perché mancano i riferimenti storici. I media digitali sono sempre più visivi perché è più facile presidiare l’attenzione con codici veloci e autosaturanti, è raro che qualcuno usi i new media per filtrare paradigmi storici. L’immagine attuale, nella sua usabilità strumentale, pretende di spiegare tutto, lascia poco tempo all’indulgenza, alla riflessione e all’immaginazione (non è un caso che “immaginazione” sia una parola con la stessa radice). Ma, a differenza del testo, può essere rapidamente sostituita – quando già ha svolto l’interazione, quindi ha già liberato i suoi dati indicali – da un’altra immagine o da un altro video. Sulle piattaforme digitali, se si considera il modello economico che le sostiene, ciò è perfettamente comprensibile, così come è chiaro che la tradizione del Novecento - che noi chiamiamo il secolo collage - è stata totalmente assorbita dalle pratiche di sedimentazione mediale: se lo scopo è sfruttare il “tempo in piattaforma”, per creare più interazioni possibili, tale processo è il modo più semplice, per quanto si possa moralmente condannare il meccanismo del montaggio. Il montaggio conforma e metabolizza tutto: sviluppa un’automazione dello sguardo.

Oggi, i media sono ossessionati dal presidio dell’attenzione e, quindi, della «pura immagine»: lo scarto letterario che va incontro a un loro bisogno, non al nostro, si presenta come digitalizzazione di contenuti standard. In sostanza, i media attrezzano una sorta di “grillroom dei contenuti”, dove le vivande hanno tutte lo stesso sapore, perché a loro non interessa più farci riflettere. Detto ciò, per chi ci sa fare con l’arte, si aprono straordinarie opportunità nel «campo della visualità». Se tutto è “potenzialità creativa illuminata dall’immagine”, è molto più semplice, con un singolo richiamo, aprire una crepa nelle nostre zoppicanti consapevolezze. Quando irrompe sulla scena una nuova forma di montaggio, manualmente digitale o veicolatamente robotica, è come se riuscisse a sfondare la pedissequa esposizione che ci troviamo dinanzi. E troviamo, legittimamente, il modo per giustificare tutto. Oggi ci sono molte più informazioni in un museo d’arte contemporanea che viaggia sulla rete, o nei profili degli utenti di FB, che in un telegiornale. Ma pure la vostra timeline della galleria di immagini, che compare sui social, molto spesso ricalca la sequenza del telegiornale del giorno.

Il ruolo dell’artista è completamente cambiato, egli si è ritrovato come un lavoratore della grande dispensa creativa e, a sua volta, deve stare attento a non farsi dettare l’agenda dai media, o peggio, cercare una provocazione gratuita per puri fini di visibilità mediatica. Come accennavo prima, mentre in molti si affannano a definire il presente come l’esito di una rivoluzione compiuta, la cosiddetta “rivoluzione digitale”, personalmente credo che siamo davvero all’inizio, in una sorta di “antico” in cui i problemi che vediamo, e che spesso sono imputati alla rete, in realtà non sono causati da essa, ma semplicemente rivelati dal determinismo, mal interpretato, dei new media. Inoltre, gran parte dei conflitti che questi fanno emergere riguardano lo scontro tra chi resiste al cambiamento, per difendere le posizioni acquisite in èra analogica, e chi considera il cambiamento la premessa dell’affermazione dei propri diritti.

Questa, ovviamente, è una opportunità ambigua: pensiamo alle minoranze tra le identità di genere, e alla loro conquistata centralità nel dibattito pubblico; pensiamo alle doppie facce di un’installazione multimediale; pensiamo al triplo o al quadruplo risultato delle vicende artistiche del post-medialismo. O agli artisti privi di garanzie. O a questioni concettuali che erano tabù fino a pochi anni fa, come la “performance concettuale” assorbita dai new media. La scelta non era, come qualcuno pensa, tra un mondo di sola immagine e uno agitato nel complesso di colpe del teatro. Eravamo tempestosi anche prima, anche al tempo di Friedrich o di Holderlin. Semmai, pur tra molte complessità, se vogliamo adesso possiamo ascoltare le difficoltà di tutti a trovare lo spazio di una vera identità artistica. E saranno gli inquieti come Carlo Caloro o Fabrizio Federici a cambiare le cose. Storicamente fare arte a mano era solo un’abilità, un mestiere, come fare il falegname, l’agricoltore, o l’operaio metallurgico. Non era certamente un’occupazione per le fasce più basse della società, ma nemmeno per l'élite intellettuale: gli uomini che coltivavano il potere erano ritenuti troppo puri per farlo. D’altronde i profeti e i messia non dipinsero mai niente. I punti di forza di un leader carismatico, e che non sapeva né dipingere e né barcamenarsi tra le arti sorelle, riguardavano le occasioni della nuova artisticità. Molti dei greci benestanti non capivano cosa fosse la scultura o la cultura delle arti visive. Infatti, la parola scuola deriva dal greco che significa tempo libero, quiete e riposo e sorregge proprio l’idea di tempo artistico, che si è andato costruendo nel nostro contemporaneo.

La nuova popolarità espressiva si intrattiene con banchetti espositivi, che sostituiscono le vecchie esposizioni. Montare e assemblare cultura digitale, favorire meme e cucina virtuale, rappresenta la più alta libertà di espressione concessaci dal drip engagement artistico contemporaneo. Quando dipingiamo al pc, abbiamo l’impressione di entrare in contatto con noi stessi. Quando «dipingiamo con l’assemblaggio» andiamo veloci e visualizziamo molto, ma raggiungiamo una connessione apparentemente più vera – con noi stessi e con i nostri pensieri più intimi - quando appoggiamo la mano sullo schermo.

Già sono stati prodotti autotreni che non hanno bisogno di nocchiere autostradale, in grado di restare a debita distanza dalle altre autovetture, e preparati per ottimizzare il consumo di carburante; si prevede che saranno milioni di autisti nel mondo che perderanno il lavoro nei prossimi anni, così come è già avvenuto per le agenzie di viaggio o per le librerie. Se nel passato era possibile per chi perdeva il lavoro riciclarsi in un’altra occupazione più sofisticata, a partire dal 2000 con il passaggio dalla Old Economy alla New Economy, questo non è più praticabile. In definitiva mentre robot e intelligenza artificiale riducono l’occupazione, non solo in fabbrica, ma anche negli uffici, dall’altra le imprese della gig economy (termine che deriva dalla musica jazz, dalla contrazione di engagement, per indicare l’ingaggio per una serata) del genere artistico-NFT e proto-meme offrono lavoretti promettendo utili colossali e per di più sfuggendo al mondo del fisco. In quanto ad allergie per la speculazione finanziaria, le imprese artistiche della gig economy sono in buona compagnia con i nuovi creativi. Ma questa situazione non solo provoca distorsione e concorrenza sleale con le attività tradizionali e mancato gettito psichico per il paese dove l’arte svolge il proprio business, ma soprattutto porta ad accollare alle Imprese Mediali i costi sociali della sfera creativa di una gig economy, che nel frattempo si è trasformata in una gig-art creativity. Purtroppo ciò che ci piace da curator ci scandalizza da cittadini: pensateci bene, quando per risparmiare prendete una memoria artistica e consimili o vi rivolgete a google per un transito, un attraversamento in un’opera d’arte!

Questi temi sono cari a Carlo Caloro, autore di un grande ciclo di lavori che si avvale della collaborazione di un social media manager, specializzato in Storia dell’Arte! Stiamo vivendo un’epoca di profondo cambiamento - sottolinea Carlo Caloro presentando le sue opere – la terza più radicale epoca di cambiamenti della storia delle persone. La prima segnata dalla scoperta del fuoco, la seconda l’invenzione della ruota che rese possibili comunicazioni fino a quel momento impensabili. E oggi il punto di svolta della rete: una rivoluzione digitale, così potente e vertiginosa, che sta imprimendo a tutta la nostra vita un cambiamento senza eguali; un cambiamento così forte che, come prima cosa, è riuscita ad invalidare i principali paradigmi che l’hanno voluta strumentalizzare, come la Net Art. In questo mondo di grandi cambiamenti, per certi versi positivi, ma che provocano anche grandi diseguaglianze, l’arte contemporanea riesce ad affermare solo di voler credere alla tautologia della sua disaffermazione e, nella sua capacità di reagire e di adattarsi in maniera intelligente a tutte queste nuove sollecitazioni, riesce quasi sempre ad affermare solo la sua stessa immaterialità. Soprattutto, quando essa reagisce secondo i nuovi criteri che l’epoca impone, superando i metodi di ieri – creatività reclamistica contro creatività pubblicitaria; strategia contro strategia – e sposando, invece, le opportunità che la rete ci porta e ci impone, il messaggio è chiaro: blockchain di icone, simulazioni di espressioni, orizzonti di nuovi e vecchi immaginari, ortodossia immateriale in contraddizione con qualsiasi net art. Nell’etica dell’antinomia immaginaria, nel rispetto della distanza da qualsiasi confronto distopico, nell’aiuto di ciò che vive solo nell’illusione, nella solidarietà e nella gratitudine dell’irrealizzabile: l’arte, anche nel digitale, si compie per sparire, per raggiungere il suo stadio definitivo di virtualizzazione!

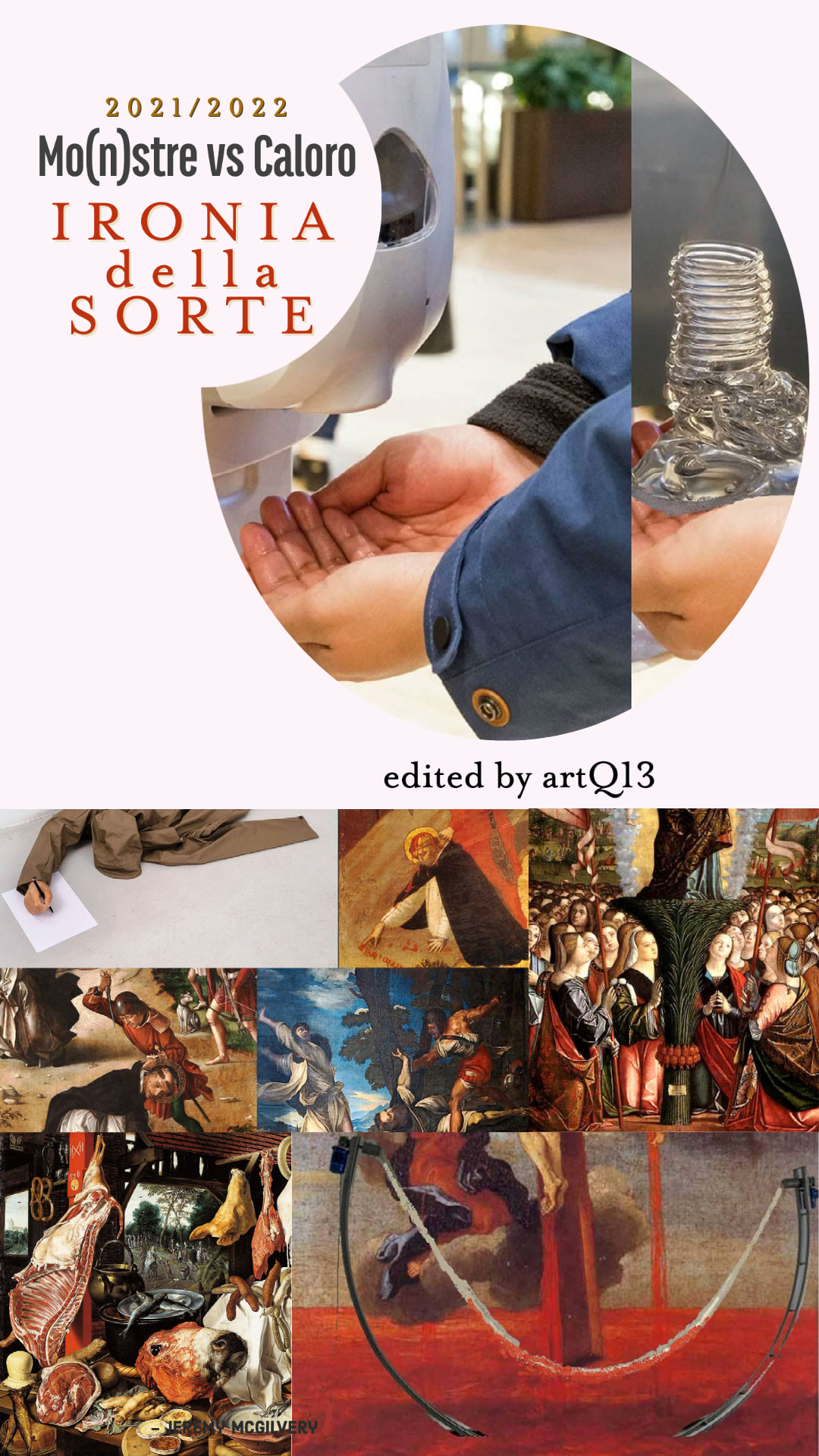

Da questa prospettiva, il lavoro di Carlo Caloro, accompagnato da Fabrizio Federici, Irony of Fate, può essere anche l’ispirazione per dar vita a imprese artistiche in grado di conciliare l’economia del meme con la strategia dell’assemblaggio, l’estetica del Rinascimento con l’etica di un Nuovo Medioevo. Come a tutti gli artisti dell’immagine complessa, a Caloro piace giocare con le immagini, i concetti e gli oggetti suoi e di altri, collegarli, rovesciarli, ambiguizzarli, estrofletterli, monetizzarli, proporli con altre strutture, con altre significazioni, quelle che prendono un diverso senso nella sua logica, una logica che è per prima cosa visiva. Questo è palese ai curatori che seguono le sue sperimentazioni e lo sarà anche ai critici delle belle opere raccolte in questa esposizione. Ma - a differenza di un puro artista concettuale o di un architetto della decorazione, o ancora di un ingegnere del tempo perso - le sequenze mimetiche di Carlo Caloro acquistano significato dalle contestualità che le accompagnano. Qui l’uso della fotografia, dell’archivio, della documentazione, del type di riconoscimento dell’immagine e della scrittura, si piegano ad una sceneggiatura di senso. Ecco allora una prima chiave di lettura dell’opera di questo curioso artista di confine e dei suoi processi cognitivi: anziché semplificare la miscela costruttiva, riducendola a poche variabili ricorrenti, lo scopo di Carlo Caloro è di ricreare la complessità dell’arte “visuale memetica”, evitando di violare la trascrivibilità del meme, così come implementa il meme con la trascrizione. Qui i piani giocano un ruolo fondamentale, le fasi del costruito si congiungono a quelle del montaggio vivo, profondità e superficie sono giocate sulla virtualità infinita degli schermi. Carlo Caloro interviene sulla scrittura scenica dell’immagine, trasformandola in scrittura visiva digitale: le immagini e le oggettualità catturate dalla macchina fotografica, o dall’assemblaggio costruttivo dei corpi ordinati o contrapposti, possono essere incontrati dallo sguardo solo se si accetta che essi, sempre si contestualizzano a vicenda. Una volta accettato questo, ci si può avventurare oltre. Si può dimostrare che, a saper guardare e ascoltare, in una qualsiasi impressione o trascrizione da meme c’è sempre più dell’assemblaggio e più dell'immagine stessa, che compare in una trascrizione storico-topica. Con Caloro si scopre l’importanza anche delle fonti silenziose, degli sguardi, degli oggetti che riempiono le installazioni, delle mediazioni e delle scene interrotte e subito dimenticate. Non è un caso, che nelle opere qui raccolte vengano menzionati e spesso descritti strumenti riguardanti storie diverse: ombre di cadaveri, sagome di suicidi e di morti ammazzati, bassorilievi di thriller, analogie di torture, nascite preistoriche e morti rinascimentali, strumenti auratici e ingrandimenti di calici, residui anatomici e arti senza vita, tentativi di disegno e braccia che raccontano semiotiche e lettere interrotte, “cristi” svelati e santi nascosti dall’occultamento delle annunciazioni, strumenti di recisione e spettri di statue antiche, teste mortali e carnevali della fede, crocifissioni mistiche e deposizioni dell’arte povera, angeli cordiali e torsioni della corda divina, bassorilievi beati e sculture alchemiche, popoli migratori e frigoriferi pubblicitari, bestiario umano e macello disumano, avventura biotica e disavventura macrobiotica, modelle che danno la schiena allo spettatore e saccheggiatori di miti, percorsi semiologici e pentagoni ermetici.

Carlo Caloro è un ricercatore infaticabile, che sa che qualsiasi elemento del contesto può dimostrarsi l’anello mancante di una catena interpretativa, digitale eppure reale. Per Caloro, tutto conta e tutto canta! O meglio, qualsiasi meme e qualsiasi oggetto, a cui ha dato origine e senso, potrebbero contare e quindi essere rilevante proprio per interpretare noi stessi e gli altri, noi stessi e i media che ci circondano nella vita quotidiana e in quel sottoinsieme che chiamiamo vita digitale e del web, sfiorando il sono-visivo filmico. Con i suoi attraversamenti, supportati da Federici, Carlo Caloro ci aiuta a ri-vedere la Storia, a rivisitare e ri-analizzare il mondo artistico popolato da capitoli interi di iconografia e iconologia, ma anche da sculture, da icone di successo, da installazioni teatrali con cui ci comunica anche quello che egli stesso non voleva intenzionalmente spettacolarizzare.

di Gabriele Perretta

Qual è la reale entità dell’inganno artistico che subiamo o «pro.creiamo»? Soprattutto in quei settori dove circola tanta astrattezza? Maggiori sono gli interessi e le seduzioni iconiche e particolarmente crudele potrebbe risultare il raggiro perpetrato ai danni delle migliaia di “creativi potenziali” che si aggirano tra le popolazioni di Android. Nell’ultimo anno negli Stati Uniti, 300.000 persone hanno scelto di inserire i dati circa le loro mansioni in un sito che verifica le loro attitudini e versatilità operative, per valutare il rischio che corrono di perdere il lavoro a causa dell’automazione e dei robot. A lanciare l’allarme nel 2013, erano stati Carl Benedikt Frey e Michael A. Osborne, i quali in uno studio avevano previsto che, nel giro di dieci o venti anni, circa il 47% dei posti di lavoro negli Stati Uniti sarebbe stato completamente automatizzato.

Un allarme eccessivo? C’è chi risponde a queste previsioni, considerate allarmistiche, segnalando come nel 1870 circa l’80% dell’intera forza lavoro statunitense fosse impiegata nell’agricoltura; successivamente, a seguito dell’introduzione dei trattori, e quindi dell’agricoltura estensiva, si verificò un esodo biblico dalle campagne, ben raccontato da Steinbeck in Furore. In pochi anni, però, questi contadini e i loro figli trovarono occupazione nell’industria ed oggi l’agricoltura americana, con meno del 2% degli occupati, è tra le più produttive del mondo. Le macchine, i robot e l’intelligenza artificiale, secondo i faciloni, creano maggiore produttività e, quindi, maggiore benessere; nello stesso tempo chi perde lavoro lo trova nell’industria, nelle prestazioni d'opera o nel campo sempre meno indistinto dell’operatività artistica o del terzo settore? A conferma di questa tesi, viene citato il fatto che il mondo occidentale e l’industria culturale che lo relaziona è più avanzato ma anche più rischioso, più sospettoso ma anche più votato alla promessa della piena occupazione.

Tutto bene, quindi? Vogliamo o non vogliamo, ci piace o non ci piace, siamo ormai nell’era post-industriale in cui le macchine svolgono - e svolgeranno sempre più - quasi tutte le attività pratiche e ripetitive. L’unica prerogativa che resta all’essere umano è la creatività, robot permettendo. Per gli artisti – che appaiono fortunati, in questo trend - i cambiamenti hanno una doppia natura. Da un lato, dobbiamo considerare cosa è cambiato direttamente per le persone: per esempio, il fatto che i nostri occhi si posano oggi sempre più spesso su nuovi orizzonti progettuali, dove valgono regole diverse rispetto a prima. Dall’altro lato, dobbiamo considerare che la «controrivoluzione dell’industria dei media tradizionali» ha influito sulla nostra comprensione del nuovo, con la paradossale conseguenza che l’innovazione, oggi, è prevalentemente raccontata da chi la subisce, e non da chi la fa.

Dobbiamo, quindi, barcamenarci tra la nostra percezione diretta del mutamento tecnologico - dove a volte scoviamo delle opportunità per migliorare la nostra vita - e la visione distopica presente nel grido artistico dei media tradizionali e dei suoi “artigiani”, che dopo anni di dominio del nostro tempo libero si sentono “sostituiti”. L’esperienza artistica diretta è, quindi, del tutto improvvisata, la nostra reazione non è né “educata”, né “strutturata”, proprio perché mancano i riferimenti storici. I media digitali sono sempre più visivi perché è più facile presidiare l’attenzione con codici veloci e autosaturanti, è raro che qualcuno usi i new media per filtrare paradigmi storici. L’immagine attuale, nella sua usabilità strumentale, pretende di spiegare tutto, lascia poco tempo all’indulgenza, alla riflessione e all’immaginazione (non è un caso che “immaginazione” sia una parola con la stessa radice). Ma, a differenza del testo, può essere rapidamente sostituita – quando già ha svolto l’interazione, quindi ha già liberato i suoi dati indicali – da un’altra immagine o da un altro video. Sulle piattaforme digitali, se si considera il modello economico che le sostiene, ciò è perfettamente comprensibile, così come è chiaro che la tradizione del Novecento - che noi chiamiamo il secolo collage - è stata totalmente assorbita dalle pratiche di sedimentazione mediale: se lo scopo è sfruttare il “tempo in piattaforma”, per creare più interazioni possibili, tale processo è il modo più semplice, per quanto si possa moralmente condannare il meccanismo del montaggio. Il montaggio conforma e metabolizza tutto: sviluppa un’automazione dello sguardo.

Oggi, i media sono ossessionati dal presidio dell’attenzione e, quindi, della «pura immagine»: lo scarto letterario che va incontro a un loro bisogno, non al nostro, si presenta come digitalizzazione di contenuti standard. In sostanza, i media attrezzano una sorta di “grillroom dei contenuti”, dove le vivande hanno tutte lo stesso sapore, perché a loro non interessa più farci riflettere. Detto ciò, per chi ci sa fare con l’arte, si aprono straordinarie opportunità nel «campo della visualità». Se tutto è “potenzialità creativa illuminata dall’immagine”, è molto più semplice, con un singolo richiamo, aprire una crepa nelle nostre zoppicanti consapevolezze. Quando irrompe sulla scena una nuova forma di montaggio, manualmente digitale o veicolatamente robotica, è come se riuscisse a sfondare la pedissequa esposizione che ci troviamo dinanzi. E troviamo, legittimamente, il modo per giustificare tutto. Oggi ci sono molte più informazioni in un museo d’arte contemporanea che viaggia sulla rete, o nei profili degli utenti di FB, che in un telegiornale. Ma pure la vostra timeline della galleria di immagini, che compare sui social, molto spesso ricalca la sequenza del telegiornale del giorno.

Il ruolo dell’artista è completamente cambiato, egli si è ritrovato come un lavoratore della grande dispensa creativa e, a sua volta, deve stare attento a non farsi dettare l’agenda dai media, o peggio, cercare una provocazione gratuita per puri fini di visibilità mediatica. Come accennavo prima, mentre in molti si affannano a definire il presente come l’esito di una rivoluzione compiuta, la cosiddetta “rivoluzione digitale”, personalmente credo che siamo davvero all’inizio, in una sorta di “antico” in cui i problemi che vediamo, e che spesso sono imputati alla rete, in realtà non sono causati da essa, ma semplicemente rivelati dal determinismo, mal interpretato, dei new media. Inoltre, gran parte dei conflitti che questi fanno emergere riguardano lo scontro tra chi resiste al cambiamento, per difendere le posizioni acquisite in èra analogica, e chi considera il cambiamento la premessa dell’affermazione dei propri diritti.

Questa, ovviamente, è una opportunità ambigua: pensiamo alle minoranze tra le identità di genere, e alla loro conquistata centralità nel dibattito pubblico; pensiamo alle doppie facce di un’installazione multimediale; pensiamo al triplo o al quadruplo risultato delle vicende artistiche del post-medialismo. O agli artisti privi di garanzie. O a questioni concettuali che erano tabù fino a pochi anni fa, come la “performance concettuale” assorbita dai new media. La scelta non era, come qualcuno pensa, tra un mondo di sola immagine e uno agitato nel complesso di colpe del teatro. Eravamo tempestosi anche prima, anche al tempo di Friedrich o di Holderlin. Semmai, pur tra molte complessità, se vogliamo adesso possiamo ascoltare le difficoltà di tutti a trovare lo spazio di una vera identità artistica. E saranno gli inquieti come Carlo Caloro o Fabrizio Federici a cambiare le cose. Storicamente fare arte a mano era solo un’abilità, un mestiere, come fare il falegname, l’agricoltore, o l’operaio metallurgico. Non era certamente un’occupazione per le fasce più basse della società, ma nemmeno per l'élite intellettuale: gli uomini che coltivavano il potere erano ritenuti troppo puri per farlo. D’altronde i profeti e i messia non dipinsero mai niente. I punti di forza di un leader carismatico, e che non sapeva né dipingere e né barcamenarsi tra le arti sorelle, riguardavano le occasioni della nuova artisticità. Molti dei greci benestanti non capivano cosa fosse la scultura o la cultura delle arti visive. Infatti, la parola scuola deriva dal greco che significa tempo libero, quiete e riposo e sorregge proprio l’idea di tempo artistico, che si è andato costruendo nel nostro contemporaneo.

La nuova popolarità espressiva si intrattiene con banchetti espositivi, che sostituiscono le vecchie esposizioni. Montare e assemblare cultura digitale, favorire meme e cucina virtuale, rappresenta la più alta libertà di espressione concessaci dal drip engagement artistico contemporaneo. Quando dipingiamo al pc, abbiamo l’impressione di entrare in contatto con noi stessi. Quando «dipingiamo con l’assemblaggio» andiamo veloci e visualizziamo molto, ma raggiungiamo una connessione apparentemente più vera – con noi stessi e con i nostri pensieri più intimi - quando appoggiamo la mano sullo schermo.

Già sono stati prodotti autotreni che non hanno bisogno di nocchiere autostradale, in grado di restare a debita distanza dalle altre autovetture, e preparati per ottimizzare il consumo di carburante; si prevede che saranno milioni di autisti nel mondo che perderanno il lavoro nei prossimi anni, così come è già avvenuto per le agenzie di viaggio o per le librerie. Se nel passato era possibile per chi perdeva il lavoro riciclarsi in un’altra occupazione più sofisticata, a partire dal 2000 con il passaggio dalla Old Economy alla New Economy, questo non è più praticabile. In definitiva mentre robot e intelligenza artificiale riducono l’occupazione, non solo in fabbrica, ma anche negli uffici, dall’altra le imprese della gig economy (termine che deriva dalla musica jazz, dalla contrazione di engagement, per indicare l’ingaggio per una serata) del genere artistico-NFT e proto-meme offrono lavoretti promettendo utili colossali e per di più sfuggendo al mondo del fisco. In quanto ad allergie per la speculazione finanziaria, le imprese artistiche della gig economy sono in buona compagnia con i nuovi creativi. Ma questa situazione non solo provoca distorsione e concorrenza sleale con le attività tradizionali e mancato gettito psichico per il paese dove l’arte svolge il proprio business, ma soprattutto porta ad accollare alle Imprese Mediali i costi sociali della sfera creativa di una gig economy, che nel frattempo si è trasformata in una gig-art creativity. Purtroppo ciò che ci piace da curator ci scandalizza da cittadini: pensateci bene, quando per risparmiare prendete una memoria artistica e consimili o vi rivolgete a google per un transito, un attraversamento in un’opera d’arte!

Questi temi sono cari a Carlo Caloro, autore di un grande ciclo di lavori che si avvale della collaborazione di un social media manager, specializzato in Storia dell’Arte! Stiamo vivendo un’epoca di profondo cambiamento - sottolinea Carlo Caloro presentando le sue opere – la terza più radicale epoca di cambiamenti della storia delle persone. La prima segnata dalla scoperta del fuoco, la seconda l’invenzione della ruota che rese possibili comunicazioni fino a quel momento impensabili. E oggi il punto di svolta della rete: una rivoluzione digitale, così potente e vertiginosa, che sta imprimendo a tutta la nostra vita un cambiamento senza eguali; un cambiamento così forte che, come prima cosa, è riuscita ad invalidare i principali paradigmi che l’hanno voluta strumentalizzare, come la Net Art. In questo mondo di grandi cambiamenti, per certi versi positivi, ma che provocano anche grandi diseguaglianze, l’arte contemporanea riesce ad affermare solo di voler credere alla tautologia della sua disaffermazione e, nella sua capacità di reagire e di adattarsi in maniera intelligente a tutte queste nuove sollecitazioni, riesce quasi sempre ad affermare solo la sua stessa immaterialità. Soprattutto, quando essa reagisce secondo i nuovi criteri che l’epoca impone, superando i metodi di ieri – creatività reclamistica contro creatività pubblicitaria; strategia contro strategia – e sposando, invece, le opportunità che la rete ci porta e ci impone, il messaggio è chiaro: blockchain di icone, simulazioni di espressioni, orizzonti di nuovi e vecchi immaginari, ortodossia immateriale in contraddizione con qualsiasi net art. Nell’etica dell’antinomia immaginaria, nel rispetto della distanza da qualsiasi confronto distopico, nell’aiuto di ciò che vive solo nell’illusione, nella solidarietà e nella gratitudine dell’irrealizzabile: l’arte, anche nel digitale, si compie per sparire, per raggiungere il suo stadio definitivo di virtualizzazione!

Da questa prospettiva, il lavoro di Carlo Caloro, accompagnato da Fabrizio Federici, Irony of Fate, può essere anche l’ispirazione per dar vita a imprese artistiche in grado di conciliare l’economia del meme con la strategia dell’assemblaggio, l’estetica del Rinascimento con l’etica di un Nuovo Medioevo. Come a tutti gli artisti dell’immagine complessa, a Caloro piace giocare con le immagini, i concetti e gli oggetti suoi e di altri, collegarli, rovesciarli, ambiguizzarli, estrofletterli, monetizzarli, proporli con altre strutture, con altre significazioni, quelle che prendono un diverso senso nella sua logica, una logica che è per prima cosa visiva. Questo è palese ai curatori che seguono le sue sperimentazioni e lo sarà anche ai critici delle belle opere raccolte in questa esposizione. Ma - a differenza di un puro artista concettuale o di un architetto della decorazione, o ancora di un ingegnere del tempo perso - le sequenze mimetiche di Carlo Caloro acquistano significato dalle contestualità che le accompagnano. Qui l’uso della fotografia, dell’archivio, della documentazione, del type di riconoscimento dell’immagine e della scrittura, si piegano ad una sceneggiatura di senso. Ecco allora una prima chiave di lettura dell’opera di questo curioso artista di confine e dei suoi processi cognitivi: anziché semplificare la miscela costruttiva, riducendola a poche variabili ricorrenti, lo scopo di Carlo Caloro è di ricreare la complessità dell’arte “visuale memetica”, evitando di violare la trascrivibilità del meme, così come implementa il meme con la trascrizione. Qui i piani giocano un ruolo fondamentale, le fasi del costruito si congiungono a quelle del montaggio vivo, profondità e superficie sono giocate sulla virtualità infinita degli schermi. Carlo Caloro interviene sulla scrittura scenica dell’immagine, trasformandola in scrittura visiva digitale: le immagini e le oggettualità catturate dalla macchina fotografica, o dall’assemblaggio costruttivo dei corpi ordinati o contrapposti, possono essere incontrati dallo sguardo solo se si accetta che essi, sempre si contestualizzano a vicenda. Una volta accettato questo, ci si può avventurare oltre. Si può dimostrare che, a saper guardare e ascoltare, in una qualsiasi impressione o trascrizione da meme c’è sempre più dell’assemblaggio e più dell'immagine stessa, che compare in una trascrizione storico-topica. Con Caloro si scopre l’importanza anche delle fonti silenziose, degli sguardi, degli oggetti che riempiono le installazioni, delle mediazioni e delle scene interrotte e subito dimenticate. Non è un caso, che nelle opere qui raccolte vengano menzionati e spesso descritti strumenti riguardanti storie diverse: ombre di cadaveri, sagome di suicidi e di morti ammazzati, bassorilievi di thriller, analogie di torture, nascite preistoriche e morti rinascimentali, strumenti auratici e ingrandimenti di calici, residui anatomici e arti senza vita, tentativi di disegno e braccia che raccontano semiotiche e lettere interrotte, “cristi” svelati e santi nascosti dall’occultamento delle annunciazioni, strumenti di recisione e spettri di statue antiche, teste mortali e carnevali della fede, crocifissioni mistiche e deposizioni dell’arte povera, angeli cordiali e torsioni della corda divina, bassorilievi beati e sculture alchemiche, popoli migratori e frigoriferi pubblicitari, bestiario umano e macello disumano, avventura biotica e disavventura macrobiotica, modelle che danno la schiena allo spettatore e saccheggiatori di miti, percorsi semiologici e pentagoni ermetici.

Carlo Caloro è un ricercatore infaticabile, che sa che qualsiasi elemento del contesto può dimostrarsi l’anello mancante di una catena interpretativa, digitale eppure reale. Per Caloro, tutto conta e tutto canta! O meglio, qualsiasi meme e qualsiasi oggetto, a cui ha dato origine e senso, potrebbero contare e quindi essere rilevante proprio per interpretare noi stessi e gli altri, noi stessi e i media che ci circondano nella vita quotidiana e in quel sottoinsieme che chiamiamo vita digitale e del web, sfiorando il sono-visivo filmico. Con i suoi attraversamenti, supportati da Federici, Carlo Caloro ci aiuta a ri-vedere la Storia, a rivisitare e ri-analizzare il mondo artistico popolato da capitoli interi di iconografia e iconologia, ma anche da sculture, da icone di successo, da installazioni teatrali con cui ci comunica anche quello che egli stesso non voleva intenzionalmente spettacolarizzare.

Carlo Caloro: "Non solo intenzional.mente"

by Gabriele Perretta

What is the true nature of the artistic deception that we live through, or “pro-create"? Particularly in those areas where so much abstractness abounds? The greater the interests and the iconic seductions, the more cruel the deception perpetrated against the thousands of "potential creatives" who wander among the populations of the Android could be. Over the last year, 300 000 people in the United States have chosen to enter their work data on a website that verifies their attitudes and professional versatility, in order to assess the risk they run of losing their jobs to automation and robots. It was Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne who first sounded the alarm about this in 2013, in a study which predicted that within 10 or 20 years around 47% of jobs in the United States would be fully automated.

Is this a case of excessive alarm? There are those who respond to these “alarmist” forecasts by pointing out that in 1870 about 80% of the entire U.S. workforce was employed in agriculture; subsequently, following the introduction of tractors, and then extensive farming, there was a biblical -scale mass exodus from the countryside (well-recounted by Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath). In a few years, however, those farmers and the generations that came after them found employment in manufacturing and today, with less than 2% of the workforce, American agriculture is among the most productive in the world. Machines, robots and Artificial Intelligence, according to those in favour, create greater productivity and, therefore, greater well-being; that said, will those who lose their jobs really find other work in manufacturing, in the service industry or in the increasingly less indistinct field of the arts, or the third sector? Those who wish to confirm this theory cite the fact that the western world and the culture industry related to it is more advanced but also more precarious; more wary but also more devoted to the promise of full employment.

So, it’s nothing to worry about, then? Whether we like it or not, we are now in the post-industrial era in which machines perform — and will increasingly perform — almost all practical and repetitive activities. The only prerogative left to human beings is creativity, robots permitting. For artists — who appear to be lucky, in terms of this trend — the changes have a dual nature. On one hand, we have to consider what direct changes people have experienced: for instance, the fact that we are now increasingly seeing new design horizons, where the rules of the game have changed, compared to the past. On the other hand, we have to consider that the "counter-revolution of the traditional media industry" has affected our understanding of the new, with the paradoxical consequence that, today, innovation is mainly narrated by those who experience it, and not by those who create it.

We must, therefore, juggle between our direct perception of technological change — where we might discover opportunities to improve our lives — and the dystopian vision of the same, present in the artistic outcry of the traditional media and its "artisans", who after years of dominating our free time now feel "replaced". Direct artistic experience is, therefore, entirely improvised, our reaction is neither "educated" nor "structured", precisely because historical references are missing. Digital media is increasingly visual because it is easier to capture attention with fast and self-saturating codes; it is rare for someone to use new media to filter historical paradigms. The current image, in its instrumental usability, claims to explain everything, leaving little time for indulgence, reflection and imagination (it is no coincidence that “image” and "imagination" share the same root). But, unlike text, it can quickly be replaced — when it has already played out the interaction, so it has already released its indicative data — by another image or video. On digital platforms, if we consider the economic model that supports them, this is perfectly understandable, just as it is clear that the tradition of the 20th century — which we call the collage century — has been totally absorbed by the practices of media sedimentation: if the aim is to exploit the "time on the platform” and to create as many interactions as possible, such a process is the easiest way, however much one may morally condemn the mechanism of montage. Editing conforms and metabolizes everything: it develops an automation of the gaze.

Today, the media is obsessed with dominating our attention and, therefore, with the "pure image": a literary off-cut that meets their needs, not ours, presented as the digitization of standard content. In essence, the media are setting up a sort of "content grill-room”, where everything has the same flavour, because they are no longer interested in making us think. That said, for those who know how to work with art, there are extraordinary opportunities in the "field of visuality". If everything is "creative potentiality illuminated by the image", it is much easier, with a single reference, to let the light in through the cracks of our weakened awareness. When a new form of montage bursts onto the scene, be it manually digital or vehicularly robotic, it is as if it succeeds in breaking through the unoriginal exposure that we find ourselves faced with. And we find a legitimate way to justify everything. Today, there is much more information to be found in a contemporary art museum than by surfing net, or in the profiles of Facebook users, than on the TV news. But even your social media image gallery timeline very often follows the sequence of the day's news.

The role of the artist has completely changed, having found themselves as workers in a vast creative ‘pantry’ and, in turn, they must be careful not to let the media dictate their agenda, or worse, seek gratuitous provocation for purely media visibility purposes. As I mentioned earlier, while many are quick to define the present as the outcome of an accomplished revolution, the so-called "digital revolution", I personally believe that we are really at the beginning, in a sort of "antiquity" in which the problems we see, and which are often blamed on the internet, are actually not caused by it, but simply revealed by the misinterpreted determinism of the new media. Moreover, most of the conflicts that these bring out concern the clash between those who resist change, in order to defend the positions acquired in the analogical era, and those who consider change the premise of the affirmation of their rights.

This, of course, presents an ambiguous opportunity: let's think about minorities among gender identities, and their hard-won centrality in public debate; let's think about the dual nature of a multimedia installation; let's think about the multiple potential outcomes of the artistic events of post-medialism. Or artists, without guarantees. Or conceptual issues that were taboo until a few years ago, such as "conceptual performance” — since accepted by new media. The choice was not, as some think, between a world purely of images and one mixed up in the theater's guilt complex. Things were tumultuous before that, even in the time of Friedrich or Holderlin. If anything, despite the many complexities involved, if we want to, we now can hear about everyone's difficulties in finding a space for their true artistic identity. And it will be the restless ones like Carlo Caloro or Fabrizio Federici who will change things. Historically, making art by hand was just a skill: a trade, like being a carpenter, a farmer, or a metalworker. It was certainly not an occupation for the lower strata of society, but neither was it for the intellectual elite; men who cultivated power were deemed too pure to do so. Then again, prophets and messiahs never painted anything. The strengths of a charismatic leader, and one who could neither paint nor get by on the sister arts, were in the opportunities for new artistry. Many of the wealthy Greeks did not understand what sculpture or visual arts culture was. In fact, the word “school” comes from the Greek word meaning free time — quiet and rest — and it supports the very idea of artistic time, which has been building up in contemporary times.

This new expressive popularity entertains itself with exhibition ‘banquets’, which have replaced the old style of exhibition: mounting and assembling digital culture, favoring memes and virtual ‘cuisine’, represents the highest freedom of expression granted to us by contemporary artistic drip engagement. When we paint on a computer, we have the impression of getting in touch with ourselves. When we "paint with assembly" we move quickly and visualize a great deal, but we achieve a seemingly truer connection — with ourselves and our innermost thoughts — when we place our hand on the screen.

Self-driving trucks have already been produced, and are able to maintain a safe distance from other cars as well as optimize fuel consumption; millions of drivers worldwide are expected to lose their jobs in the coming years, just as travel agencies or bookstores have already done. While in the past it was possible for those losing their job to ‘recycle’ themselves into another, more sophisticated occupation — starting with the shift from the Old Economy to the New Economy in 2000 — this is no longer feasible. Ultimately, while robots and A.I. reduce employment numbers, not only in factories but also in offices, on the other hand, gig economy companies (a term that derives from jazz music, meaning a contract of engagement for one evening) of the artistic-NFT and proto-meme genre offer small jobs promising colossal profits and, what’s more, escaping the world of taxation. As far as an aversion to financial speculation is concerned, the artistic enterprises of the gig economy are in good company with the new creatives. But this situation not only causes distortion and unfair competition with traditional activities and a lack of ‘psychic revenue’ for the country where the art is carried out, but above all it leads to media companies bearing the social costs of the creative sphere of a gig economy, which in the meantime has turned into a gig-art creativity.

These themes are close to Carlo Caloro, author of a broad range of works — created in collaboration with a social media manager who specialises in Art History!

In presenting his works, Caloro highlights that we are living in an era of profound change, the third most radical era of change in human history: the first was marked by the discovery of fire; the second by the invention of the wheel, rendering possible communications that were previously unthinkable; and today, the turning point of the internet — a digital revolution so powerful and dizzying that is imprinting an unparalleled change on all our lives. A change so strong that, firstly, has managed to invalidate the main paradigms that wanted to instrumentalize it, such as Net Art. In this world of great changes — in some ways positive, but in others the source of great inequality — contemporary art can only affirm that it wants to believe in the tautology of its disaffirmation and, in its ability to react and adapt intelligently to these new stresses, it almost always only manages to affirm its own immateriality. Above all, when it reacts according to the new criteria imposed by the era, taking over from the methods of yesterday — advertising creativity versus advertising creativity; strategy versus strategy — and marrying, instead, the opportunities that the network brings us and imposes on us, the message is clear: blockchains of icons, simulations of expressions, horizons of new and old imagery, immaterial orthodoxy in contradiction with any net art. In the ethics of the imaginary antinomy, out of respect for the distance from any dystopian comparison, in aid of what lives only in illusion, in solidarity and gratitude towards the unrealizable: even in digital form, art is designed to disappear, to reach its final stage of virtualization!

From this perspective, the work of Carlo Caloro, accompanied by Fabrizio Federici, Irony of Fate, can also be the inspiration which gives rise to artistic enterprises capable of reconciling the economy of the meme with the strategy of the assemblage, the aesthetics of the Renaissance with the ethics of the New Middle Ages. Like all the artists of the complex image, Caloro likes to play with images, concepts and objects of his own and of others, connecting them, overturning them, making them ambiguous, extroverting them, monetizing them, proposing them with other structures, with other meanings, those that take on a different meaning in his logic — a logic that is first and foremost visual. This is evident to the curators who follow his experiments and it will also be evident to the critics of the beautiful works collected in this exhibition. But, unlike a purely conceptual artist or an architect of decoration, or even an engineer of lost time, Carlo Caloro's mimetic sequences acquire meaning from the contexts that surround them. Here the use of photography, archive, documentation, the type of image recognition and writing are shaped by a script of meaning. Here, then, is the first key to interpreting the work of this curious borderline artist and his cognitive processes: instead of simplifying the constructive mixture and reducing it to a few recurring variables, Carlo Caloro's aim is to recreate the complexity of "memetic visual" art, avoiding violating the transcribability of the meme, just as he implements the meme with transcription. Here different planes play a fundamental role, the phases of the constructed join those of the living montage, depth and surface are played on the infinite virtuality of the screens. Carlo Caloro intervenes in the scenic writing of the image, transforming it into digital visual writing: the images and the objects captured by the camera, or by the constructive assembly of ordered or opposed bodies, can be encountered by the gaze only if we accept that they always contextualize each other. Once this has been accepted, one can venture further. One can demonstrate that, if one knows how to look and listen, in any impression or transcription from a meme there is always more than the assembly and more than the image itself, which appears in a historical-topical transcription. With Caloro one discovers the importance of silent sources, of glances, of the objects that fill the installations, of mediations and of scenes that are interrupted and immediately forgotten. It is not by chance that in the works collected here, instruments concerning different stories are mentioned and often described: shadows of corpses; silhouettes of suicides and murder victims; bas-reliefs of thrillers; analogies of tortures; prehistoric births and renaissance deaths; auratic instruments and enlarged chalices; anatomical residues and lifeless limbs; attempts at drawing and arms that represent semiotics and interrupted letters; unveiled "Christs" and saints, hidden behind concealed annunciations; cutting instruments and spectres of ancient statues; mortal heads and carnivals of faith; mystical crucifixions and poor art depositions; friendly angels and twists of the divine rope; blessed bas-reliefs and alchemic sculptures; migratory peoples and refrigerator adverts; human bestiary and inhuman slaughter; biotic adventure and macrobiotic misadventure; models who turn their backs on the spectator; plunderers of myths, semiological paths and hermetic pentagons.

Carlo Caloro is a tireless researcher, who knows that any element in context can prove to be the missing link in an interpretative chain, digital and yet real. For Caloro, everything counts and everything sings! Or rather, any meme and any object, to which he has given origin and meaning, could count and therefore be relevant precisely in order to interpret ourselves and others, ourselves and the media that surrounds us in everyday life and in that subset that we call digital and web life, touching on the filmic-visual. Supported by Federici, Carlo Caloro’s ‘crossings over’ help us to re-envisage History, to revisit and re-analyze the artistic world populated by whole chapters of iconography and iconology, but also by sculptures, successful icons and theatrical installations with which he also communicates to us what the artist himself intentionally did not render spectacular.

by Gabriele Perretta

What is the true nature of the artistic deception that we live through, or “pro-create"? Particularly in those areas where so much abstractness abounds? The greater the interests and the iconic seductions, the more cruel the deception perpetrated against the thousands of "potential creatives" who wander among the populations of the Android could be. Over the last year, 300 000 people in the United States have chosen to enter their work data on a website that verifies their attitudes and professional versatility, in order to assess the risk they run of losing their jobs to automation and robots. It was Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne who first sounded the alarm about this in 2013, in a study which predicted that within 10 or 20 years around 47% of jobs in the United States would be fully automated.

Is this a case of excessive alarm? There are those who respond to these “alarmist” forecasts by pointing out that in 1870 about 80% of the entire U.S. workforce was employed in agriculture; subsequently, following the introduction of tractors, and then extensive farming, there was a biblical -scale mass exodus from the countryside (well-recounted by Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath). In a few years, however, those farmers and the generations that came after them found employment in manufacturing and today, with less than 2% of the workforce, American agriculture is among the most productive in the world. Machines, robots and Artificial Intelligence, according to those in favour, create greater productivity and, therefore, greater well-being; that said, will those who lose their jobs really find other work in manufacturing, in the service industry or in the increasingly less indistinct field of the arts, or the third sector? Those who wish to confirm this theory cite the fact that the western world and the culture industry related to it is more advanced but also more precarious; more wary but also more devoted to the promise of full employment.

So, it’s nothing to worry about, then? Whether we like it or not, we are now in the post-industrial era in which machines perform — and will increasingly perform — almost all practical and repetitive activities. The only prerogative left to human beings is creativity, robots permitting. For artists — who appear to be lucky, in terms of this trend — the changes have a dual nature. On one hand, we have to consider what direct changes people have experienced: for instance, the fact that we are now increasingly seeing new design horizons, where the rules of the game have changed, compared to the past. On the other hand, we have to consider that the "counter-revolution of the traditional media industry" has affected our understanding of the new, with the paradoxical consequence that, today, innovation is mainly narrated by those who experience it, and not by those who create it.

We must, therefore, juggle between our direct perception of technological change — where we might discover opportunities to improve our lives — and the dystopian vision of the same, present in the artistic outcry of the traditional media and its "artisans", who after years of dominating our free time now feel "replaced". Direct artistic experience is, therefore, entirely improvised, our reaction is neither "educated" nor "structured", precisely because historical references are missing. Digital media is increasingly visual because it is easier to capture attention with fast and self-saturating codes; it is rare for someone to use new media to filter historical paradigms. The current image, in its instrumental usability, claims to explain everything, leaving little time for indulgence, reflection and imagination (it is no coincidence that “image” and "imagination" share the same root). But, unlike text, it can quickly be replaced — when it has already played out the interaction, so it has already released its indicative data — by another image or video. On digital platforms, if we consider the economic model that supports them, this is perfectly understandable, just as it is clear that the tradition of the 20th century — which we call the collage century — has been totally absorbed by the practices of media sedimentation: if the aim is to exploit the "time on the platform” and to create as many interactions as possible, such a process is the easiest way, however much one may morally condemn the mechanism of montage. Editing conforms and metabolizes everything: it develops an automation of the gaze.

Today, the media is obsessed with dominating our attention and, therefore, with the "pure image": a literary off-cut that meets their needs, not ours, presented as the digitization of standard content. In essence, the media are setting up a sort of "content grill-room”, where everything has the same flavour, because they are no longer interested in making us think. That said, for those who know how to work with art, there are extraordinary opportunities in the "field of visuality". If everything is "creative potentiality illuminated by the image", it is much easier, with a single reference, to let the light in through the cracks of our weakened awareness. When a new form of montage bursts onto the scene, be it manually digital or vehicularly robotic, it is as if it succeeds in breaking through the unoriginal exposure that we find ourselves faced with. And we find a legitimate way to justify everything. Today, there is much more information to be found in a contemporary art museum than by surfing net, or in the profiles of Facebook users, than on the TV news. But even your social media image gallery timeline very often follows the sequence of the day's news.

The role of the artist has completely changed, having found themselves as workers in a vast creative ‘pantry’ and, in turn, they must be careful not to let the media dictate their agenda, or worse, seek gratuitous provocation for purely media visibility purposes. As I mentioned earlier, while many are quick to define the present as the outcome of an accomplished revolution, the so-called "digital revolution", I personally believe that we are really at the beginning, in a sort of "antiquity" in which the problems we see, and which are often blamed on the internet, are actually not caused by it, but simply revealed by the misinterpreted determinism of the new media. Moreover, most of the conflicts that these bring out concern the clash between those who resist change, in order to defend the positions acquired in the analogical era, and those who consider change the premise of the affirmation of their rights.

This, of course, presents an ambiguous opportunity: let's think about minorities among gender identities, and their hard-won centrality in public debate; let's think about the dual nature of a multimedia installation; let's think about the multiple potential outcomes of the artistic events of post-medialism. Or artists, without guarantees. Or conceptual issues that were taboo until a few years ago, such as "conceptual performance” — since accepted by new media. The choice was not, as some think, between a world purely of images and one mixed up in the theater's guilt complex. Things were tumultuous before that, even in the time of Friedrich or Holderlin. If anything, despite the many complexities involved, if we want to, we now can hear about everyone's difficulties in finding a space for their true artistic identity. And it will be the restless ones like Carlo Caloro or Fabrizio Federici who will change things. Historically, making art by hand was just a skill: a trade, like being a carpenter, a farmer, or a metalworker. It was certainly not an occupation for the lower strata of society, but neither was it for the intellectual elite; men who cultivated power were deemed too pure to do so. Then again, prophets and messiahs never painted anything. The strengths of a charismatic leader, and one who could neither paint nor get by on the sister arts, were in the opportunities for new artistry. Many of the wealthy Greeks did not understand what sculpture or visual arts culture was. In fact, the word “school” comes from the Greek word meaning free time — quiet and rest — and it supports the very idea of artistic time, which has been building up in contemporary times.

This new expressive popularity entertains itself with exhibition ‘banquets’, which have replaced the old style of exhibition: mounting and assembling digital culture, favoring memes and virtual ‘cuisine’, represents the highest freedom of expression granted to us by contemporary artistic drip engagement. When we paint on a computer, we have the impression of getting in touch with ourselves. When we "paint with assembly" we move quickly and visualize a great deal, but we achieve a seemingly truer connection — with ourselves and our innermost thoughts — when we place our hand on the screen.

Self-driving trucks have already been produced, and are able to maintain a safe distance from other cars as well as optimize fuel consumption; millions of drivers worldwide are expected to lose their jobs in the coming years, just as travel agencies or bookstores have already done. While in the past it was possible for those losing their job to ‘recycle’ themselves into another, more sophisticated occupation — starting with the shift from the Old Economy to the New Economy in 2000 — this is no longer feasible. Ultimately, while robots and A.I. reduce employment numbers, not only in factories but also in offices, on the other hand, gig economy companies (a term that derives from jazz music, meaning a contract of engagement for one evening) of the artistic-NFT and proto-meme genre offer small jobs promising colossal profits and, what’s more, escaping the world of taxation. As far as an aversion to financial speculation is concerned, the artistic enterprises of the gig economy are in good company with the new creatives. But this situation not only causes distortion and unfair competition with traditional activities and a lack of ‘psychic revenue’ for the country where the art is carried out, but above all it leads to media companies bearing the social costs of the creative sphere of a gig economy, which in the meantime has turned into a gig-art creativity.

These themes are close to Carlo Caloro, author of a broad range of works — created in collaboration with a social media manager who specialises in Art History!

In presenting his works, Caloro highlights that we are living in an era of profound change, the third most radical era of change in human history: the first was marked by the discovery of fire; the second by the invention of the wheel, rendering possible communications that were previously unthinkable; and today, the turning point of the internet — a digital revolution so powerful and dizzying that is imprinting an unparalleled change on all our lives. A change so strong that, firstly, has managed to invalidate the main paradigms that wanted to instrumentalize it, such as Net Art. In this world of great changes — in some ways positive, but in others the source of great inequality — contemporary art can only affirm that it wants to believe in the tautology of its disaffirmation and, in its ability to react and adapt intelligently to these new stresses, it almost always only manages to affirm its own immateriality. Above all, when it reacts according to the new criteria imposed by the era, taking over from the methods of yesterday — advertising creativity versus advertising creativity; strategy versus strategy — and marrying, instead, the opportunities that the network brings us and imposes on us, the message is clear: blockchains of icons, simulations of expressions, horizons of new and old imagery, immaterial orthodoxy in contradiction with any net art. In the ethics of the imaginary antinomy, out of respect for the distance from any dystopian comparison, in aid of what lives only in illusion, in solidarity and gratitude towards the unrealizable: even in digital form, art is designed to disappear, to reach its final stage of virtualization!

From this perspective, the work of Carlo Caloro, accompanied by Fabrizio Federici, Irony of Fate, can also be the inspiration which gives rise to artistic enterprises capable of reconciling the economy of the meme with the strategy of the assemblage, the aesthetics of the Renaissance with the ethics of the New Middle Ages. Like all the artists of the complex image, Caloro likes to play with images, concepts and objects of his own and of others, connecting them, overturning them, making them ambiguous, extroverting them, monetizing them, proposing them with other structures, with other meanings, those that take on a different meaning in his logic — a logic that is first and foremost visual. This is evident to the curators who follow his experiments and it will also be evident to the critics of the beautiful works collected in this exhibition. But, unlike a purely conceptual artist or an architect of decoration, or even an engineer of lost time, Carlo Caloro's mimetic sequences acquire meaning from the contexts that surround them. Here the use of photography, archive, documentation, the type of image recognition and writing are shaped by a script of meaning. Here, then, is the first key to interpreting the work of this curious borderline artist and his cognitive processes: instead of simplifying the constructive mixture and reducing it to a few recurring variables, Carlo Caloro's aim is to recreate the complexity of "memetic visual" art, avoiding violating the transcribability of the meme, just as he implements the meme with transcription. Here different planes play a fundamental role, the phases of the constructed join those of the living montage, depth and surface are played on the infinite virtuality of the screens. Carlo Caloro intervenes in the scenic writing of the image, transforming it into digital visual writing: the images and the objects captured by the camera, or by the constructive assembly of ordered or opposed bodies, can be encountered by the gaze only if we accept that they always contextualize each other. Once this has been accepted, one can venture further. One can demonstrate that, if one knows how to look and listen, in any impression or transcription from a meme there is always more than the assembly and more than the image itself, which appears in a historical-topical transcription. With Caloro one discovers the importance of silent sources, of glances, of the objects that fill the installations, of mediations and of scenes that are interrupted and immediately forgotten. It is not by chance that in the works collected here, instruments concerning different stories are mentioned and often described: shadows of corpses; silhouettes of suicides and murder victims; bas-reliefs of thrillers; analogies of tortures; prehistoric births and renaissance deaths; auratic instruments and enlarged chalices; anatomical residues and lifeless limbs; attempts at drawing and arms that represent semiotics and interrupted letters; unveiled "Christs" and saints, hidden behind concealed annunciations; cutting instruments and spectres of ancient statues; mortal heads and carnivals of faith; mystical crucifixions and poor art depositions; friendly angels and twists of the divine rope; blessed bas-reliefs and alchemic sculptures; migratory peoples and refrigerator adverts; human bestiary and inhuman slaughter; biotic adventure and macrobiotic misadventure; models who turn their backs on the spectator; plunderers of myths, semiological paths and hermetic pentagons.

Carlo Caloro is a tireless researcher, who knows that any element in context can prove to be the missing link in an interpretative chain, digital and yet real. For Caloro, everything counts and everything sings! Or rather, any meme and any object, to which he has given origin and meaning, could count and therefore be relevant precisely in order to interpret ourselves and others, ourselves and the media that surrounds us in everyday life and in that subset that we call digital and web life, touching on the filmic-visual. Supported by Federici, Carlo Caloro’s ‘crossings over’ help us to re-envisage History, to revisit and re-analyze the artistic world populated by whole chapters of iconography and iconology, but also by sculptures, successful icons and theatrical installations with which he also communicates to us what the artist himself intentionally did not render spectacular.